A FUTURE SALVO

The world of science and the art world are both in crisis. Their crises are equally profound, and equally distressing. But their effects are not produced in the same way in each case.

The crisis running through the world of science has the appearance of a problem of status. Researchers are witnessing their investigative freedoms restricted through funding on a project-by-project basis. The time they have to devote to reflection is dwindling because of the race to publish. Engineers are witnessing the value of their degrees decline in the eyes of businesses. Their intelligence is being challenged by machines. Today their role is that of someone who executes projects. Overall, scientific speech is being devalued. But this problem of status is having trouble masking a crisis of paradigm. It was long believed that scientists produce truths useful to all. With the scandal of corrupt expert opinions, it was learned that sometimes they produce a criminal falsehood. With people’s newfound ecological awareness, we learned that they also produced an uninhabitable world.

Nowhere is harder hit than universities by the end of a model in which scientists are scholars whose knowledge is held to be immense and whose claims are held to be universal. Not only is knowledge omnipresent on the Internet, but its obsolescence has increased to the point that the lifespan of a scientific assessment is now measured in months. Finally, the dizzying inflation of fields of knowledge in our day and age has cruelly diminished the universal claims of scientific knowledge. This knowledge has become one form of knowledge among others which to modern eyes appear more useful, or simply more exciting.

The crisis the art world is going through has also taken on the appearance of a problem of status. Admittedly, this problem is not new. It has long existed in the form of a devaluation that is not always easy to perceive. The status of the artist is in flux and critical and experimental art practices continue to lose value. A variety of realities lie behind this fact. We might note that some efforts to democratise art have devalued the intrinsic worth of artists by confusing creativity and art, such that everyone becomes an artist. We might note also those public policies which tend to exploit art for economic ends, for urban renewal or to develop tourism without ever taking into account art’s fundamental value and its aesthetic and critical contributions. We are thinking also of certain new cultural industries which devalue independent artistic practices and claim the status of artwork for their products, whose aim is consensus and popularity above all else.

None of the realities with a role in this situation is directly attempting to devalue artistic practices, but they are certainly the symptom of something broken. Each of them reduces the visibility of art in the public sphere. They blur the boundaries between what is art and what is something other than art. The ensuing indeterminacy brings discredit to present-day artistic practices in the eyes of the public, making its reception and outreach more difficult. Perhaps we should ask ourselves whether we still wish to have a critical relationship with the world which would make it possible to consider it in all its complexity.

At the same time as we observe these crises, we are witnesses to an intensification of the relations between art and science. The number of initiatives which take up these themes is increasing or placing themselves under its aegis. The worlds of art and science are joining with increasing frequency. Unfortunately, their relations remain tinged with a mixture of ignorance and attraction. We can only observe that the two worlds are becoming even closer in the form of mutual exploitation. Each is standing firm in its logic and methods.

In the face of this observation, we cannot remain powerless. We are cultural workers, artists and scientists who have joined together under the banner of a space for contemporary art: Sporobole. In our own way, each of us believes in art and science. We meet in thinking that there is more to be saved than to be destroyed in this crisis. We share a desire to carry this out.

Our intention is to contribute to bringing new ideas to these worlds, by drawing from each the resources which will make this transformation possible.

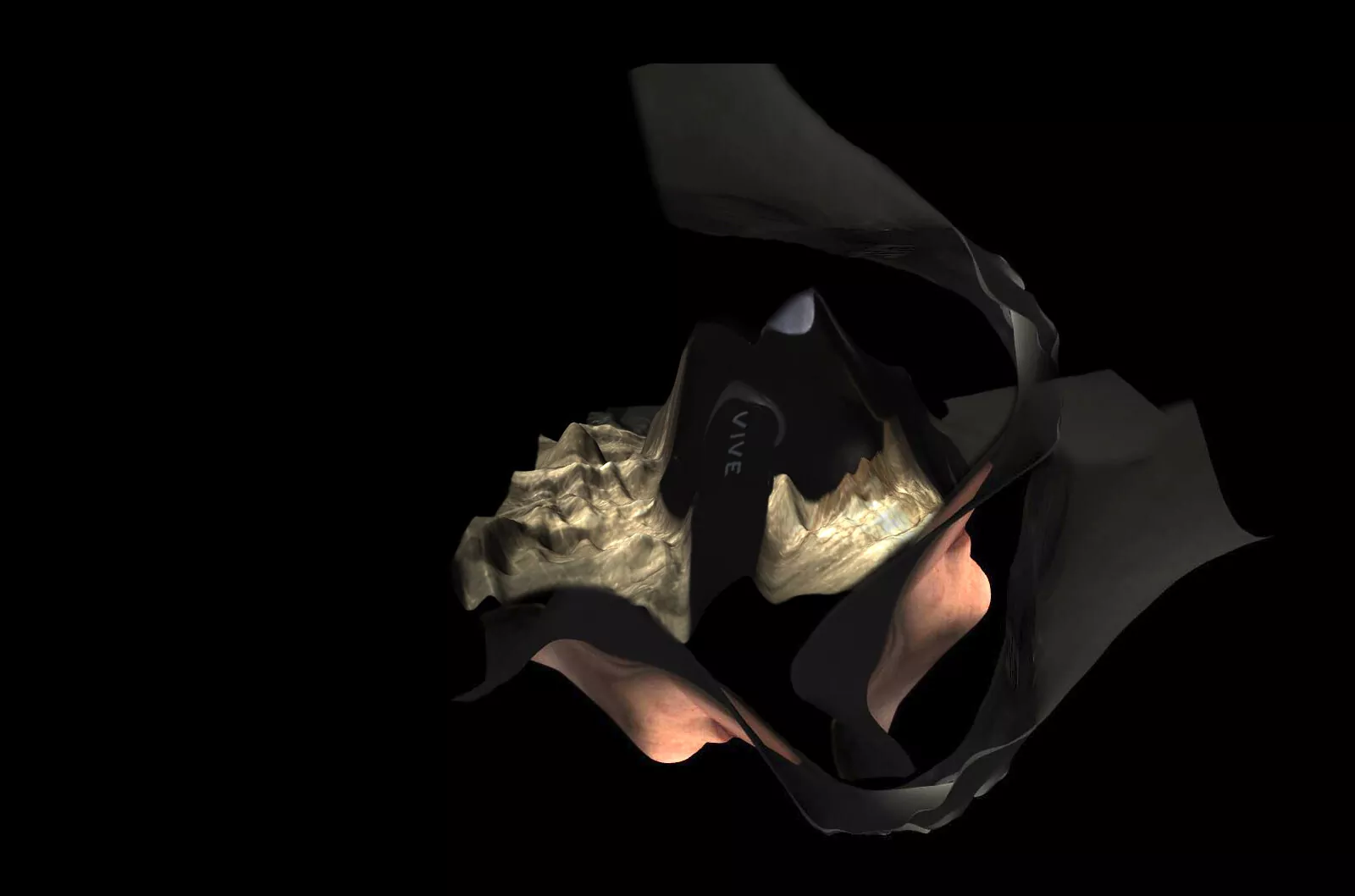

To carry this out we are establishing – in the context of Sporobole and its mandate of re-asserting contemporary artistic practices – the conditions for an egalitarian research space where these practices are not used as a tool. This space will be a site for reflection, publication and experimentation. It will serve to explore how science works with art and vice versa. The ways in which they influence each other, draw on each other and affect each other. The task will be to contribute to broadening the range of interactions between these two worlds in order to counteract their natural tendency to exploit themselves.

We have chosen two topics to begin this research. These are themes which interest us and which we believe can constitute motifs for powerful forms of renewal.

The first topic is entitled “Knowledge and Counter-knowledge”.

Art has the ability to generate multiple forms of knowledge: it is polysemous and plurivocal. As many avenues of reflection can emanate from a work of art as there are individuals who wish to think about it. These forms of knowledge are diverse and operate at different levels. Often implicit and intuitive, they also manifest themselves through the senses. Today the language of artworks is highly diverse: this language is no longer merely a part of the visible world, but also takes the form of interactivity, sound, immersion, etc. Conversely, science generally tends towards univocal responses or even truths. Forms of scientific knowledge have a basic responsibility: to contribute to building the world, to laying its foundations.

Our task will be to see how contemporary artistic practices – both the artworks and the creative processes – generate singular forms of knowledge which intersect with scientific knowledge and contribute to embracing the world in which we live in all its complexity. By examining particular artworks or by interrogating artistic practices, it will be possible to identify elements for understanding art-science dynamics and to observe the mechanics of knowledge production.

The second topic is entitled “Efficiency and Inefficiency”.

Efficiency is a part of the scientific paradigm. It is a virtue which scientists readily don and is, moreover, willingly granted to them. Through technology, in fact, science transforms the world in a highly efficient manner. The extent to which this efficiency is without limits is a question we will ask ourselves.

The art world, for its part, does not recognise the word “efficiency” as familiar to it. And yet, if we examine it a little closer, we must attribute a kind of efficiency to art. A critical efficiency, first of all: what else interrogates as continuously and as profoundly our way of being in the world? But not only that. There is a very practical efficiency, for example, in the way artists manage their projects. These projects are most often indeterminate and unfold in a time which is that of their gestation. The extent to which the artistic gesture is not highly efficient is another question we will ask ourselves. Naturally, we will ask whether one artist’s efficiency could not be another’s resource.

“With each collapse of proofs the poet responds with a future salvo”– René Char

Miguel Aubouy, Nathalie Bachand & Éric Desmarais

Photo credits: Tanya St-Pierre